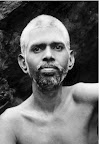

Shri Atmananda's teachings

Reading through the teachings of Shri Atmananda Krishna Menon is like reading Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. A page of inspiring quotations is located here . Following are some pieces from the book.

5. WHAT IS THE CONTENT OF THE INTERVAL BETWEEN MENTATIONS?

Let us examine our own casual statements regarding our daily experiences. For example, we say: 'He comes', 'He sits', 'He goes', and so on. In these statements, 'coming', 'sitting' and 'going' are somehow extraneous to 'him'. As such, they do not at all go into the make of 'him'.

'He' alone stands unqualified through all time, continuing without a break. So it is

this pure 'he' or 'I' (or Consciousness) which shines through and in between all

thoughts, feelings, perceptions and states. During this interval (between mentations),

one has no thought of the state in which one happens to be. So here, one is Peace

itself; and that is the 'I', in its pure state.

Suppose you see a beautiful picture, painted on white paper. On closely examining

the picture, you will be able to discover some parts of it where the original colour of

the paper appears, unaffected by the shades of the picture. This proves to you the

existence of the paper behind the picture, as its background. On further examination,

you will see that the picture is nothing but the paper.

So also, if you succeed in discovering yourself between two mentations, you easily

come to the conclusion that you are in the mentations as well.

6. WHAT IS THE MEANING OF 'I'? (6)

The same word, used in similar contexts, cannot carry different meanings with differ-

ent persons. When I say 'I' meaning 'my body', another understands it in the same

sense, meaning 'my body'. But when the other person uses the same word 'I', he

means 'his body', which is entirely different from 'my body'.

Thus, in the case of everyone, the bodies meant are different; but the word used is

the same 'I', always. So the 'I' must mean: either the individual bodies of all men –

which is ludicrous – or it must evidently mean no body at all.

The latter being the only possible alternative, the 'I' must necessarily mean that

changeless principle in which every body appears and disappears. This is the real

meaning of 'I', even in our daily traffic with the world.

7. WHAT IS IT THAT APPEARS AS WORLD? (7)

As soon as we wake up from deep sleep, the existence of a ready-made world –

including our own bodies – confronts us. To examine it closely, we utilize our sense

organs straightaway – one by one, relying on their superficial evidence without a

thought.

The organ of sight asserts that the world is only form and nothing else; the organ of

hearing that the world is only sound and nothing else; and so on. Each organ thus

asserts the world as its sole and particular object. In effect, each sense organ contra-

dicts the evidence of the other four organs, with equal force. This hopeless mess of

contradictory evidence, and the stubborn denial by each of the sense organs of the

others' evidence, form positive proof of the falsity of this world – as it appears.

But all the while, the existence of a positive something is experienced without a

break, beyond the shadow of a doubt. This, on closer analysis, is found to be that

changeless, subjective 'I'-principle or Consciousness itself.

Some quotes:

The mind is the father of all illusion.No amount of effort, taken on your own part, can ever take you to the Absolute.

Liberation is complete only when you are liberated from liberation as well.

Remembering is the only 'sin'; and that alone has to be destroyed.

'Be in Consciousness without knowing that you are in Consciousness.'

Please see:

http://www.advaita.org.uk/discourses/atmananda/atmananda1.htm

http://www.advaita.org.uk/discourses/atmananda/atmananda_quotes.htm

http://geocities.com/rahul_kumar/atmananda.html

How to retreat into the 'I' principle

What do you mean when you say 'I'? It does not at all mean the body, senses or mind.

It is pure experience itself – in other words, the end of all knowledge or feeling.

First of all, see that the body, senses and mind are your objects and that you are always the changeless subject, distinct and separate from the objects. The objects are present only when they are perceived. But I exist, always changeless, whether perceptions occur or not, extending through and beyond all states. Thus you see that you are never the body, senses or mind. Make this thought as deep and intense as possible, until you are doubly sure that the wrong identification will never recur.

Next, examine if there is anything else that does not part with the 'I'-principle, even for a moment. Yes. There is Consciousness. It never parts with the 'I'-principle, and can never be an object either. So both must mean one and the same thing. Or, in other words, 'I' is Consciousness itself. Similarly, wherever there is the 'I'-principle left alone, there is also the idea of deep peace or happiness, existing along with it.

It is universally admitted that one loves only that which gives one happiness, or that

a thing is loved only for its happiness value. Evidently, happiness itself is loved more

than that which is supposed to give happiness. It is also admitted that one loves one's

self more than anything else. So it is clear that you must be one with happiness or that

you are happiness itself. All your activities are only attempts to experience that happi-

ness or self in every experience

The ordinary man fixes a certain standard for all his worldly activities and tries to

attain it to his satisfaction. Thereby, he is only trying to experience the self in the form

of happiness, as a result of the satisfaction obtained on reaching the standard already

accepted by him.

For every perception, thought or feeling, you require the services of an instrument

suited to each activity. But to love your own self, you require no instrument at all.

Since you experience happiness by retreating into that 'I'-principle, that 'I' must be

either an object to give you happiness, which is impossible; or it must be happiness

itself. So the 'I'-principle, Peace and Consciousness are all one and the same. It is in

Peace that thoughts and feelings rise and set. This peace is very clearly expressed in

deep sleep, when the mind is not there and you are one with Consciousness and

Peace.

Pure consciousness and deep peace are your real nature. Having understood this in

the right manner, you can well give up the use of the words 'Consciousness' and

'Happiness' and invariably use 'I' to denote the Reality.

Don't be satisfied with only reducing objects into Consciousness. Don't stop there.

Reduce them further into the 'I'-principle. So also, reduce all feelings into pure

Happiness and then reduce them into the 'I'-principle. When you are sure that you

will not return to identification with the body any longer, you can very well leave off

the intermediaries of Consciousness and Happiness, and directly take the thought 'I, I,

I', subjectively.

Diversity is only in objects. Consciousness, which perceives them all, is one and

the same.

WHAT IS MY REAL GOAL? THE 'I'-PRINCIPLE

The word 'I' has the advantage of taking you direct to the core of your self. But you

must be doubly sure that you will no longer return to identification with the body.

By reducing objects into Consciousness or happiness, you come only to the brink of

experience. Reduce them further into the 'I'-principle; and then 'it', the object, and

'you', the subject, both merge into experience itself. Thus, when you find that what

you see is only yourself, the 'seeing' and 'objects' become mere empty words.

When you say the object cannot be the subject, you should take your stand not in

any of the lower planes, but in the ultimate subject 'I' itself.

In making the gross world mental, the advaitin is an idealist. But he does not stop

there. He goes further, examining the 'idea' also and proves it to be nothing but

Consciousness. Thus he goes beyond even the idealist's stand.

The realist holds that matter is real and mind is unreal, but the idealist says that

mind is real and matter is unreal. Of the two, the idealist's position is better; for when

the mind is taken away from the world, the world is not. Therefore, it can easily be

seen that the world is a thought form. It is difficult to prove the truth of the realist's

stand; for dead matter cannot decide anything.

The advaitin goes even further. Though he takes up the stand of the idealist when

examining the world, he goes beyond the idealist's position and proves that the world

and the mind, as such, are nothing but appearances and the Reality is Consciousness.

Perception proves only the existence of knowledge and not the existence of the ob-

ject. Thus the gross object is proved to be non-existent. Therefore, it is meaningless to

explain subtle perceptions as a reflection of gross perceptions. Thus all perceptions

are reduced to the ultimate 'I'-principle, through knowledge.

When a Jnyanin takes to activities of life, he 'comes out' with body, sense organs

or mind whenever he needs them; and he acts, to all appearances, like an ordinary

man, but knowing full well, all the while, that he is the Reality itself. This is not said

from the level of the Absolute.

-- Shri Atmananda See this also Gap between mentations

Bhakti and Jnana

Bhakti cripples your ego and makes you feel equal to the most insignificant blade of grass; and you conceive your God i as the conceivable Absolute. Thus, when your ego is at last lost, you automatically reach the position of the Godhead.

But jnana takes you up, step by step, by the use of discrimination or higher reason; attenuating the ego little by little each time, until the ego is dead at last. By this process, you transcend mind and duality, and reach the ultimate Reality.