One who is free from desire

sees the glory of the Self

through the tranquillity of the mind and senses

and becomes absolved from grief.

admin – Thu, 06/10/2005 – 6:09am

Do your duty, to the best of your abilities, for the Lord without any selfish motive, and remember God at all times -- before starting a work, at the completion of a task, and while inactive.

Practice to look upon all creatures as "Myself" in thought, word, and deed; and mentally bow down to them

— Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita

admin – Tue, 04/10/2005 – 1:25pm

The wandering of the mind itself is the world.

admin – Tue, 04/10/2005 – 1:22pm

Events happen, deeds are done, there is no individual doer thereof

admin – Tue, 04/10/2005 – 1:21pm

When it comes to miracle-working, the wisdom traditions of the East never seem to be able to make up their minds.

Take the last century. On one side, there was Paramahansa Yogananda. Bursting onto the scene in 1946, his now classic Autobiography of a Yogi captured the imaginations of a generation of Western seekers with thrilling tales of living spiritual supermen whose miraculous powers suddenly made our comic-book heroes look a bit less fantastical. Mysterious sages who could control the weather at will. Great masters who could fly through the air and walk through walls or appear in multiple places at once. Austere yogis with the power to read and control men's minds, muster herculean strength, and tolerate insufferable pain without flinching. Along with a few other landmark books like Baird Spaulding's Life and Teachings of the Masters of the Far East and Lama Govinda's Way of the White Clouds, Yogananda cast in our minds a vision of spiritual enlightenment in which the attainment of a kind of supernatural omnipotence was not only possible but the destiny of anyone who would take up the path of meditation in earnest.

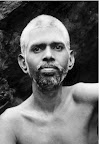

On the other side was Sri Ramana Maharshi. Hailing from the Advaita Vedanta, or nondualist, school of Hinduism, he insisted that any interest in the attainment of siddhis [supernatural powers] was not only misguided but a distraction on the path to the Ultimate Realization. "Occult powers will not bring happiness to anyone," he claimed. "They are not natural to the Self . . . and . . . not worth striving for." Supported in this view by such luminaries as Nisargadatta Maharaj and Sri Ramakrishna, who declared that the siddhis are "heaps of rubbish," he carried forward the legacy of a long tradition of mystics including even the Buddha, who warned against any attempt to work miracles.

If the wisdom coming to us from the East was split on this topic, here in the West, at least initially, the picture wasn't much different. On one hand, many psychologically and rationally inclined Westerners naturally seemed to ignore the supernatural dimensions of Indian spirituality, giving more attention to the psychological and emotional benefits of meditative practice. But on the other hand, owing mostly to the power marketing of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's Transcendental Meditation (TM) Siddhi program and Yogananda's Self-Realization Fellowship, as well as to the uncanny popularity of the miracle-working Indian God-man Sai Baba, the promise of attaining miraculous powers did find many converts. Not least among them was a growing cadre of scientifically minded seekers for whom the siddhis represented a thrilling research potential-an opportunity to prove to the scientific establishment the existence of God.

A brief survey of the East-meets-West spiritual landscape today, however, suggests that of late, the Western interest in superordinary powers has been losing some ground. Perhaps the mystics' warnings have simply had their intended effect. Perhaps the fact that Sai Baba was caught several times on film faking some of his "miracles" made former believers cynical. Or perhaps we've all just waited too long for our TM-practicing friends to actually demonstrate something that remotely passes for "yogic flying." But whatever the cause, here in the modern West, the promise of the miraculous seems to be losing its allure.

Interestingly enough, on the far shores of India, some similar trends are under way. With an increasing secularism sweeping the nation, and the Indian Rationalist Association's "Guru Busters" actively working to debunk every miracle-touting charlatan they can, anyone claiming to be able to defy the laws of nature is in for a fight. Fortunately for the faithful, at least one Indian yogi is not the least bit daunted. He calls himself "Pilot Baba," and for the past three decades he has been working to uphold the dignity and integrity of the yogic siddhi tradition by demonstrating in some very public places his miraculous powers over the world of matter.

A decorated Indian Air Force fighter pilot who saw combat in two wars and also served as personal pilot for Indira Gandhi, this military-man-turned-mahayogi regularly attracts tens of thousands of devout Hindus to witness his performances of what is traditionally known as bhugarbha samadhi or jal samadhi or Asht Lakshmi Maha Yagna samadhi. In English, what this means is that he buries himself underground, encases himself in an airtight glass box, or submerges himself under water-for days or even weeks at a time. Employing an ancient yogic technique that could best be described as a sort of human hibernation-plus, Pilot Baba is purported to be able to voluntarily shut down all bodily functions to the point that he is clinically dead, only to return to life at a pre-specified date and time-a feat that has withstood the scrutiny of at least some Western scientists. And if all this sounds like something you saw on "That's Incredible!" back in the eighties, remember that the great Yogi Kudu only spent one hour at the bottom of the pool before being fished out to much applause by John Davidson and Cathy Lee Crosby. Pilot Baba's record under water is four days, a figure which itself pales in comparison to the thirty-three days he's spent underground.

How did a celebrated air force pilot end up deciding to carry this ancient yogic tradition into the third millennium? During his visit to New York last September, I asked Pilot Baba to share his story.

As he tells it, although he never planned to be a yogi, there was a yogi who apparently had plans for him. Guiding him throughout his childhood, and miraculously saving his life more than once during his time in the air force, this mysterious holy man eventually provoked him to renounce the world and, in 1973, with the help of a group of four other sages, initiated him into the mysteries of yoga. But it wasn't until three years (and a several-thousand-mile Himalayan trek) later that those mysteries would begin to unfold in his own experience. During a period of intensive spiritual practice in and around his cave in the Himalayan wilderness, Pilot Baba made a sudden breakthrough that would change the course of his life forever. "I had been sitting on a large, exposed stone in the center of the river for several days, when I had the thought, 'Why doesn't the water flow over me without touching me?' And then it started happening. It started flowing over me and all around me without touching me." As he continued to "play with the water" over the days that followed, people from the nearby village started to gather on the shore, in awe at the spectacle they were beholding. Before long, news began to spread of this mysterious yogi who could control the flow of the river.

Some of us, upon discovering that we had the power to control the forces of nature, might be tempted to use it to improve our lot in life (or at least to rig up some supernatural plumbing for our cave). But for Pilot Baba, the effect was quite the opposite. Realizing that the human will can work wonders "if it is clear, positive, and free from desire," he began to use his newfound powers to heal the suffering people in the villages throughout his region. And as tends to happen around anyone who gains a reputation for healing, in a matter of weeks, people were lining up in droves to receive his blessing. But the miracles didn't stop there.

Indeed, as he began to test the limits of this miraculous power he had stumbled upon, it soon became apparent to him that, for all practical purposes, there were no limits. Over the course of our conversation, he shared one story after another that seemed so far beyond the reach of reason to explain that I soon felt like I was starting to occupy the world Yogananda had written about so many years before. Like the time when he was walking with a group around Mt. Kailash and a giant boulder came careening down the hill toward them and he deflected it by merely holding up his arm. Or the time when he walked on water, all the way to the center of a large lake. Or the time when a storm threatened to rain out one of his samadhi demonstrations and he used his will powers to "throw water at the ominous clouds" and send them away. Or the time he walked barefoot to the summit of one of the Himalayas' most treacherous peaks-in six hours-in order to assist a climbing party that had taken eighteen days to cover the same ground.

In all of Pilot Baba's miracle stories, it was clear that these powers are not something he takes lightly or uses frivolously. To the contrary, it seemed to almost go without saying that they should only be employed to help others or when a greater good requires it. In light of this, the fact that he has taken to publicly demonstrating samadhi seemed on the surface to be a bit of a paradox. How had these public demonstrations become so central to his work? I asked. And how had he gotten the idea to do them in the first place? As it turns out, this too had come about in response to a need, albeit a different sort of need than he had previously faced.

The year was 1978, and in a rare departure from the Himalayas, Pilot Baba had traveled to Delhi to attend a large science and yoga conference convened by the great kundalini master Gopi Krishna and attended by a handful of political leaders, a group of scientists, and many of the brightest lights in the Indian yoga world. At some point in the conference, the question of bodily control was raised. Could any of the esteemed yogis assembled demonstrate the mastery of vital function needed to survive in an airtight glass case? And when no one in the illustrious gathering volunteered, Pilot Baba, who claims he had never before attempted the feat, raised his hand. "For how many days would you like me to do it?" he asked. Wired up with vital-signs monitors, he crawled into the case, brought his heart to a stop, and for the next three days, an eager assembly looked on. Then, thirty minutes before his scheduled return, a faint heartbeat began to register on the monitor. His emergence from the case-hailed by many as a return from death-was announced in newspapers across India, and as offers to donate land, buildings, and money began to pour in, he disappeared late one night and returned to the peace of the mountains.

But he didn't stay there. In the years since that dramatic event, Pilot Baba-and more recently, his disciples-have been regularly performing public samadhis at events as well attended as India's largest spiritual festival, the Maha Kumbha Mela. This has earned him such notoriety and respect among the Hindu faithful that he was recently elected to the lofty position of Mahamandaleshwar, spiritual head of India's largest and most prominent order of renunciates, the million-strong sect of naked, ash-smeared, trident-wielding "warrior-ascetics" known as Naga Babas.

The purpose of the samadhi demonstrations, according to his organization's literature, is to promote world peace. And if you find you have to stretch to make the link between returning from the grave and creating peace on Earth, remember that it was a similar demonstration by the "Prince of Peace" two thousand years ago that kick-started one of humanity's most enduring, if not altogether peaceful, religious movements. For Pilot Baba, the connection is unambiguous. When an individual goes into samadhi, he told me, a tremendous power is released which can uplift, inspire, heal, and transform all who come into contact with it. Moreover, through the exertion of will by the yogi before entering the samadhi, that power can be directed toward a stated goal. And for Pilot Baba and all of the disciples who have dared to join him, that goal is always to generate harmony and peace between human beings.

Now, there are miracles and then there are miracles. And for most of us, the ability to shut down and restart one's vital systems, however mind-bending and miraculous, does not fall under quite the same category as flying unaided through the air or controlling the elements. If Pilot Baba really can defy all physical laws, one might ask, why doesn't he do something more dramatic just to put the skeptics to rest once and for all? In response to such questions, Pilot Baba has always insisted that the samadhi demonstrations are not about proving anything to anyone. But if the unexpected turn of events at his most recent samadhi is any indication, it does seem that of late, he has decided it might be worth sending a slightly stronger message.

It was the middle of last April in the central Indian town of Dewas, and Pilot Baba had again entered into an airtight glass case where he was to remain motionless for four days. In order to prevent the 110-degree desert heat from causing the case to explode, it had been surrounded by curtains which would be drawn back for brief darshan [viewing] periods several times each morning and evening. On the third evening, everything seemed to be proceeding as usual. But at 8pm, when the curtains were drawn open for the third time that night, "a quick hush went over the crowd." As filmmaker Andre Vaillancourt, who was there to document the event, describes it, "I squinted . . . in order to catch a glimpse of Baba. As the words [of the crowd] came to my ears, the picture came into focus: Baba is gone! Vanished! Dematerialized! Only his orange dhoti [robe] lay on the spot where he sat." Most of the journalists had gone home for the evening, so Vaillancourt was the only one to catch the event on film. But the next evening, the camera crews were all there, along with an unusually large crowd, when Pilot Baba again vanished for the 8 and 9pm darshans.

If not to prove anything, then why had he done it? "I wanted to surprise people-particularly the intellectuals," he explained to me as our conversation was drawing to a close.

The Indian Rationalist Association, of course, is unimpressed and says it won't be satisfied until Pilot Baba, or any other yogi, performs this demonstration under its supervision. And although Pilot Baba has made it clear that he is certainly not about to stoop to trying to prove God's existence to the rationalists ("Atheists have their religion, too," he states), it may well take just that for his feats to begin making headlines in the West. Whether even a "supervised" demonstration would begin to make inroads against the rationalistic leanings of contemporary spiritual America, however, is anybody's guess. And if Pilot Baba has his way, we'll all be kept guessing for a bit longer.

Courtesy: http://www.wie.org

admin – Tue, 04/10/2005 – 12:30pm

Cornering the Ego

An interesting interview with Chinese Master, Sheng-yen, on destroying the Ego, ego tricks, the state of the Buddha, the role of the teacher etc.

What is the ego according to Ch'an Buddhism?

Master Sheng-yen: In Ch'an Buddhism the idea of ego revolves around the idea of attachment or clinging. The ego originally does not exist. It is created as a result of attachment to the body and attachment to one's ideas or one's own viewpoint. But because both the body and the mind are impermanent and constantly changing over time, our attachments to them are always changing as well. And as these attachments change, the ego also changes. So from the perspective of Ch'an, the ego does not exist in the sense of being a permanent, unchanging entity. The ego does not exist independent of one's changing attachments to one's body and one's ideas.

WIE: What does it mean to go beyond the ego?

SY: There are two different ways to accomplish this transcendence of the ego. One is experiential, through experiencing the transcendence of the self. And this can be done through practice, the practice of sitting meditation and the investigation of a koan [paradoxical question]. It is possible to attain this experience without a practice, but that's very rare; most people need to do the practice. The point of this kind of practice is to essentially push the ego into a corner so that it has nowhere else to go. It cannot escape anywhere.

So the ego and the method that you are using to transcend the ego are in direct opposition to each other. As I said, the ego is based on attachment—our attachment to the body and to ideas. Therefore, the method of transcending the ego is to deal with this attachment, to put down this attachment. When the ego is cornered and has nowhere to go, the only thing one can do is to put it down. And when one puts down the ego, then that is enlightenment.

WIE: Could you explain further how facing into a koan helps to "corner the ego"?

SY: In this method, you're actually not trying to solve the koan. Rather, the method involves asking the koan to give you the answer. A koan may be like, "What is wu [nothingness]?" So you keep asking and asking the koan to give you the answer to that question. But actually, it's impossible to answer. Of course, in the process of asking, your mind will give you answers, but whatever answer you get you have to reject. And you just stay with this method—keep asking and keep rejecting whatever answer comes up in your mind. In the end you will develop a sense of doubt. You will not be able to ask the koan anymore. In fact, it'll be meaningless to ask anymore. Then there is nothing to do except to finally put down the self and that is when enlightenment appears in front of you. But if you ask the koan and you simply get tired, if you can't get an answer and so you just stop, that's not enlightenment. That's just laziness.

The second way to transcend the ego is the conceptual way. It happens when there's a sudden and complete change in one's viewpoint. It can happen, for example, when one's reading a sutra [Buddhist scripture] or listening to a dharma talk. In an instant, one can become enlightened. But for this to really work, a person has to already want to know the answer to the question, "What is ego, what is the self?" They have to already be engaged with this question in their own mind. And then, when they come across a particular sentence, they can suddenly recognize the answer and instantaneously realize enlightenment. One very good example is the Sixth Patriarch, Hui Neng. He heard one sentence from the Diamond Sutra and got enlightened. However, for people who never think about these issues and questions in their daily life, who don't care about what the ego is and have no desire to know what the self is, this won't work. Listening to a dharma lecture or reading the sutras isn't going to help them.

WIE: What is the role of the teacher in liberating the student from his or her ego?

SY: First of all, the most important thing is that the student has to really want to know what the nature of the ego is. They need to have this burning desire to know. Then, what the teacher can do is to give the students a method or a tool to investigate and show them how to go about practicing the method. Many students may have a method and not be able to use it well. So the teacher can show a student how to use their method properly and can also show the right attitude and conceptual understanding they need in going about their practice. And if the student has a strong desire to understand the nature of their real self, then the method will be helpful. They will be able to see that this self that's based on attachment is illusory. It's not real. And when they realize this, they will also see that there's no such thing as the ego.

WIE: In your recent book Subtle Wisdom, you write, "Sometimes the mind experiences something that it takes to be enlightenment, but it is actually just the ego in a very happy state." Could you explain the difference between these two experiences—between genuine enlightenment and a condition where the ego is simply, as you said, "in a very happy state"?

SY: The experience of happiness can also be a part of enlightenment; a person can feel happy whether they are enlightened or not. But usually when one is in this blissful, happy state, it is because, in that moment, one is no longer feeling burdened by one's body or by one's mind and emotions, and so one feels very at ease. However, this is not the same as liberation. One may feel very light; it doesn't mean anything. A very peaceful, blissful, happy feeling is not the same as enlightenment. Enlightenment is not being attached to any viewpoint or having any attachment to the body. There's no burden at all, and that's why one would feel happy. For example, Shakyamuni Buddha, after his enlightenment, sat under the bodhi tree for seven days to enjoy this happiness, this dharma joy from his liberation. But one can feel happiness whether one is enlightened or is not enlightened. So we need to be able to distinguish.

WIE: In your book you go on to say that this experience of the ego being in a very happy state could occur because "the ego may even be identified with the universe as a whole or with divinity." Could you explain what you mean by that?

SY: That feeling of unification with the universe is actually one kind of samadhi [meditative absorption], a result of a deep state of concentration, and when a person is at this stage, they recognize that the entire universe is the same as themselves. What happens is that one expands one's small ego outward, to include all viewpoints, to include all of the universe and everything in it. So at this point, one would no longer have individual selfish ideas or individual selfish thoughts that normally arise from the narrow, selfish ego. In fact, one may experience a tremendous power that would result from this samadhi, a power that would come from the idea that "the universe is the same as me." People who have had this kind of realization can often become very great religious leaders.

But the Buddha, after his enlightenment, did not say, "I'm the center of the universe." Neither did he say that he represented the entire universe. What he said is that the Buddha is here to encourage all sentient beings to see that ego comes from attachment, and if we can all put down this attachment, then we will be liberated. And so the Buddha sees himself as a friend, a wise friend to all sentient beings, encouraging them to understand that ego comes from attachment and encouraging everybody to practice, to put down this attachment.

So in the Buddha's nirvana, there's no more arising and no more extinguishing. There's no self—no big Self, no small self—and that is the true enlightenment. That's the enlightenment of the Buddha.

WIE: So if an individual is identified with the universe as a whole, is there still, in that case, an ego attachment that the individual hasn't given up?

SY: Yes.

WIE: Some of the great Ch'an and Zen patriarchs were reputed to have been very fierce teachers who would go to great lengths and use very extreme measures to liberate their students from their egos. In your books, you have written about how some of your own teachers were very tough with you as well. Is it because our attachment to the ego is so deep and so strong that these revered masters needed to employ such extreme measures to get their students to go beyond the ego?

SY: Actually, not everybody needs these harsh methods. The kind of method that is used has to match the needs of the individual student and the condition of the moment. Timing is very important. For example, when I teach my students, I only use harsh methods when it is necessary. Most of the time I use a lot of encouragement, especially for beginner students. It is for those who have been practicing for a while, who have a lot of confidence in their practice already but who still have this attachment to the ego, that I will use some harsher methods to help them to move forward. But it takes a very experienced, very good master to know when the time is right to use such methods.

WIE: Another passage from your book reads, "If your sense of self is strong, solid, and formidable, then there is no way you can experience enlightenment." What do you mean by this? Why is it difficult for a person with a strong sense of self or what Westerners would call "a strong ego" to experience enlightenment?

SY: It's not necessarily true that people who have a very strong ego cannot be enlightened. In fact, those who know that they have a strong ego may, in some cases, actually be very good candidates to practice the Buddha-dharma. You see, there is a type of person who is very egocentric yet at the same time has a strong desire for enlightenment. Because of this strong desire, they are naturally going to be very unhappy and dissatisfied with having a big ego, and that attitude will be good for their practice. When you have such a strong ego, you have to be willing to do something about it. So someone like this could be a good candidate for practicing and studying Ch'an.

Then there are also individuals who have what we would call a weaker or softer ego. This can help them, but only if they still have a real desire to deal with their ego. If they don't, they are not going to be any closer to enlightenment because they won't have any confidence in the practice. They won't have diligence in the practice. But if an individual has a weaker, softer ego and still understands that they need to practice diligently to deal with it, then we could say that these individuals, because they have both a strong desire for liberation and a smaller ego, are closer to enlightenment.

WIE: Today many Western spiritual teachers believe that traditional spiritual paths, including Buddhism, do not properly address all the needs of the modern seeker. In particular, they feel that people may need psychotherapy to supplement their spiritual practice in order to work out many of their emotional attachments and problems with their ego. Do you feel that the Ch'an path is incomplete when it comes to addressing the suffering of the modern seeker and that a person would be well advised to consider this dual approach—psychotherapy and spiritual practice—in their pursuit of enlightenment? Or is spiritual practice alone, if it's sincere and diligent, sufficient to free us from the ego?

SY: There are two different issues here. First, individuals who have very severe psychological problems should not use the Ch'an method. It's not good for them. If they just want to learn the beginner's sitting meditation, we will teach them and they will reap benefits from that, such as improved health. However, a person with severe problems should get a doctor to help them recover before they begin the practice of Ch'an.

But generally, for individuals who do not have severe psychiatric problems, Ch'an practice is sufficient. There's no need to get help from a psychiatrist or a therapist. In fact, sometimes psychiatrists or therapists come and seek help from me.

WIE: In the last thirty years, there have been many powerful teachers who have had profound spiritual understanding and experience and have attracted large numbers of students, but who eventually fell from grace due to corruption and scandal, sometimes in very shocking ways. Is it possible that spiritual experience and understanding could, in some cases, actually empower the ego?

SY: It's hard to say. I don't really want to comment on this. It is a problem. There are some individuals who think that they are enlightened, that they are liberated, and they also have the idea that after they're liberated, they do not need any morality; they do not need to uphold the precepts [basic obligations undertaken by Buddhists] anymore. And according to my own understanding of Buddhism—I can only speak for myself here—we follow Shakyamuni Buddha and if we look at the Buddha after he was enlightened, he didn't go and drink. He didn't go and hang out with women, sleep around and cheat people out of their money. And so that is what we follow. The Chinese Ch'an masters emphasize the importance of upholding the precepts.

WIE: For everyone, teachers and students?

SY: In the sutras, the Buddhist scriptures, they say that if you are really genuinely enlightened, you will naturally uphold the precepts.

WIE: You are a revered teacher with students in Taiwan and also Western students here in America. Some of the Western spiritual teachers and psychologists we have spoken to for this issue have said that the ego of Westerners is different from the ego of Easterners—that Westerners are more attached to an individual self and personal identity. If that's true, then theoretically, it should generally be easier for Easterners to get enlightened than it is for Westerners. Do you agree with that? Is that your experience?

SY: This is not necessarily the case. It all depends on whether you have the desire for enlightenment—whether, as I was saying, you really want to understand the nature of the ego.

WIE: You're saying that's the key to success?

SY: Yes, that's the key. You may have a weak or small ego, but if you don't care about these things and you don't have a strong desire, then you're not closer to enlightenment.

Courtesy:

http://wie.org